I KNOW I WAS THERE. I DON'T REMEMBER ANYTHING.

Behind a closed door.

Sometime in 1995, three young men contacted the Homosexual Working Group of the Revolutionary Socialist Party (GTH-PSR for short, in Portuguese). They had a proposal for the group – to together put on a gay and lesbian-themed party at the recently-opened nightclub CLIMACZ, located off the Jardim Constantino garden, in Lisbon. José Carlos Tavares, at the time spokesperson for the GTH-PSR, held a meeting with Jonas, his boyfriend and Paulo. Jonas Rio, window dresser and visual artist, was in charge of CLIMACZ' decor, located at what was once a strip club called Up and Down, and whose premises had been renovated with the help of the studio of infamous architect Tomás Taveira1. The owner, Vítor Trindade, knew a DJ João Daniel from another club, Visage, that the former ran in the beach town of Costa da Caparica, and invited him to join forces and open a new nightspot located at number 116-B of Rua Passos Manuel.

Jonas had been to the parties the GTH held at the PSR headquarters at number 268 of Rua da Palma in Lisbon.

These parties took place every Friday, and once a month were hosted by the GTH. People took something to eat

and drink, films were shown, get-togethers and simple theatrical performances were held, as well as heated

debates. “There's no fight without a party!”, Zé Carlos says to me. Which would also be a good title for this text.

Options were virtually non-existent and just as had happened with the creation of CHOR (the Revolutionary Homosexual

Collective) in 1980, as João Grosso had told us on another occasion, the fight was for the simple right to exist.

These parties at the Rua da Palma address, or at the Comuna theatre, where the GTH manifesto – A Ousadia de Quem Sabe

o que Quer [Those Who Dare to Know What They Want] – was officially announced, did little more (as if this wasn't

enough) than make spaces available to be oneself in. If no such space exists, then we shall create it.

8 months later, on November 11th, 1994, CLIMACZ would open, meticulously designed down to the finest detail from the sound system to the door handles. You went through a door all the way down to the basement. Colours would change to suit the desired mood on the night. Nothing was left to chance. Different light effects revealed what looked like sperm wriggling up towards the ceiling on these enormous columns. In the bathrooms, small speakers called out names to whoever passed by.

Joana Relvas and Xunguinha (or shouldn't that be Chumbinho?), who also did PR for Kremlin, were on the door, flanked by just two bodyguards with a metal detector – a novelty at the time – to ensure the clientele remained safe and sound. There weren't the brawls you'd usually see in places like this. Whoever went out at night at the time, knows full well what we are talking about.

CLIMACZ was open between six in the morning and midday. It was easier to get a music licence for a café than a dance club, although that wasn't the main reason for operating at that hour. House music and acid house competed with rock music as the music genres of choice in the clubs in the 1990s. João Daniel knew practically all the DJs in the land. They all bought the latest sounds he would sell from his record shop in Campo de Ourique, A Question of Time Records, on Rua do Patrocínio 28-B. João didn't want to compete with anyone. He wanted to open a space where people could go after other places closed their doors. He also wanted it to be a space where whoever worked at night could go after they finished their shift.

These were the times of Kremlin, Alcântara-Mar, Plateau, when Avenida 24 de Julho and its cross-streets teemed with people. Manel Reis did a test run for Lux at a warehouse belonging to the old Fábrica da Tabaqueira, in Marvila, at a party celebrating the 10th anniversary of Frágil, in 1992. It would be right there on the east side of Lisbon, between the future Parque das Nações and Santa Apolónia where, in 1998, Lux would open its doors. All over the country, raves were popping up and people would head to Pacha de Ofir in the north, Kadoc in the Algarve, Green Hill at Foz do Arelho, and Horta da Fonte in Cartaxo...

I came across a photo of the entrance to CLIMACZ alongside a text written by Gabriel de Oliveira Feitor, Uma Pequena História da Música Eletrónica de Dança em Portugal [A Brief History of Electronic Dance Music in Portugal], published on the site Comunidade Cultura e Arte. If this text eventually gets published online, we'll add a link to the other text (in two parts) or if it goes to print, we might include an excerpt to help us better understand how we got here:

Why was the first-ever Portuguese Gay Pride held at CLIMACZ, when there already were other spaces catering more exclusively to a LGBTQIA+ audience, and what was the importance of EDM to the LGBTQIA+ community, back then in 1995 as well as nowadays, in 2024?

Rua da Atalaia, 125

The story of our lives together began in the Bairro Alto. Rua da Atalaia was where it was at. I first met Nuno loitering outside Primas when I went to say hi to a female friend of mine. Later on, we worked at Capela on Rua da Atalaia, and then in 1998 Nuno got a job at Lux and me at Café Suave. We were still in school. Me at the Fine Arts college, Nuno at Nova. We rented our first place at no. 125 Rua da Atalaia, right above Arroz-Doce (in truth, it was the building next door), where everyone drank Pontapés na Cona (A Kick in the Cunt). Frágil was where we used to go and, if we were broke, we'd sit at the window watching who got past the door. Margarida Martins was no longer there, this was no Frágil class of '82, but it was still the place to be. Cláudia Spencer was on the door, keeping up the female quotient, and we'd dance to whatever house music or acid house Yen Sung, Vargas or Murka were spinning.

In 1982, when Manel Reis, together with Carlos Fonseca, turned an old bakery at no. 126 Rua da Atalaia, into a bar which would forever change the course of history in Lisbon, it was a long before it became our stomping ground. Bairro Alto nightlife was shrouded in darkness, a place where prostitutes rubbed shoulders with a bohemian enclave of journalists and Fine Arts students in the neighbourhood taverns. Trumps had opened years before, in November 1980, but it wasn't the first to do so in Príncipe Real. In 1975, following the April 25th revolution, Finalmente Club had already opened at no. 38 Rua da Palmeira, and Guida Scarllaty's - pseudonym of Carlos Ferreira - Scarllaty Club, at Rua de São Marçal, in a stretch of nightlife known for its drag shows, frequented by the LGBT community and their allies.

When we started seeing each other and going out at night, there were all kinds of places, but maybe it was the artistic community we found so fascinating at Frágil that would end up making this the place where our memories as a couple were created. The stellar taste in music we were able to hear in places like Frágil and the people from all walks of life who came together there (a privileged elite, we know now, but anyway...) made a deep impression on us, at the beginning of the 1990s.

“Frágil was a space where we could be free. Until then, no such place existed for us all. And that was huge. Lisbon was so backward.” (Miguel Esteves Cardoso) “Frágil was where the idea of a nightlife all began, when going out was frowned upon and seen as something disreputable, by which Manuel Reis changed the rules. He created a night for having fun and partying, surreal, hedonistic and free. It was as cosmopolitan as it was possible to be in such an uncool city, a place we liked to believe was different from everywhere else.” (Cabrita Reis)

It was the possible night for us, the night we discovered for ourselves. Some time ago, reading the book História da Noite Gay de Lisboa [A History of Lisbon's Gay Nightlife] we commented, “This happened in our day, but we weren't there.” One story among others. We didn't go to the party at CLIMACZ, actually. But we are here, now.

No Fight Without a Party

“Do you know why you are here?”, “Do you know what June 28th stands for?” “Have you heard of Stonewall?”, asks invited host and member of Abraço Francisco Borges. Maria José Campos offers a clue, “He's the guy with the pony tail sat next to Margarida Martins on the Manuela Moura Guedes show about AIDS, Raios e Coriscos. He died a few years ago. The last I heard of him, he was working at the Estoril Open and doing voiceovers.”

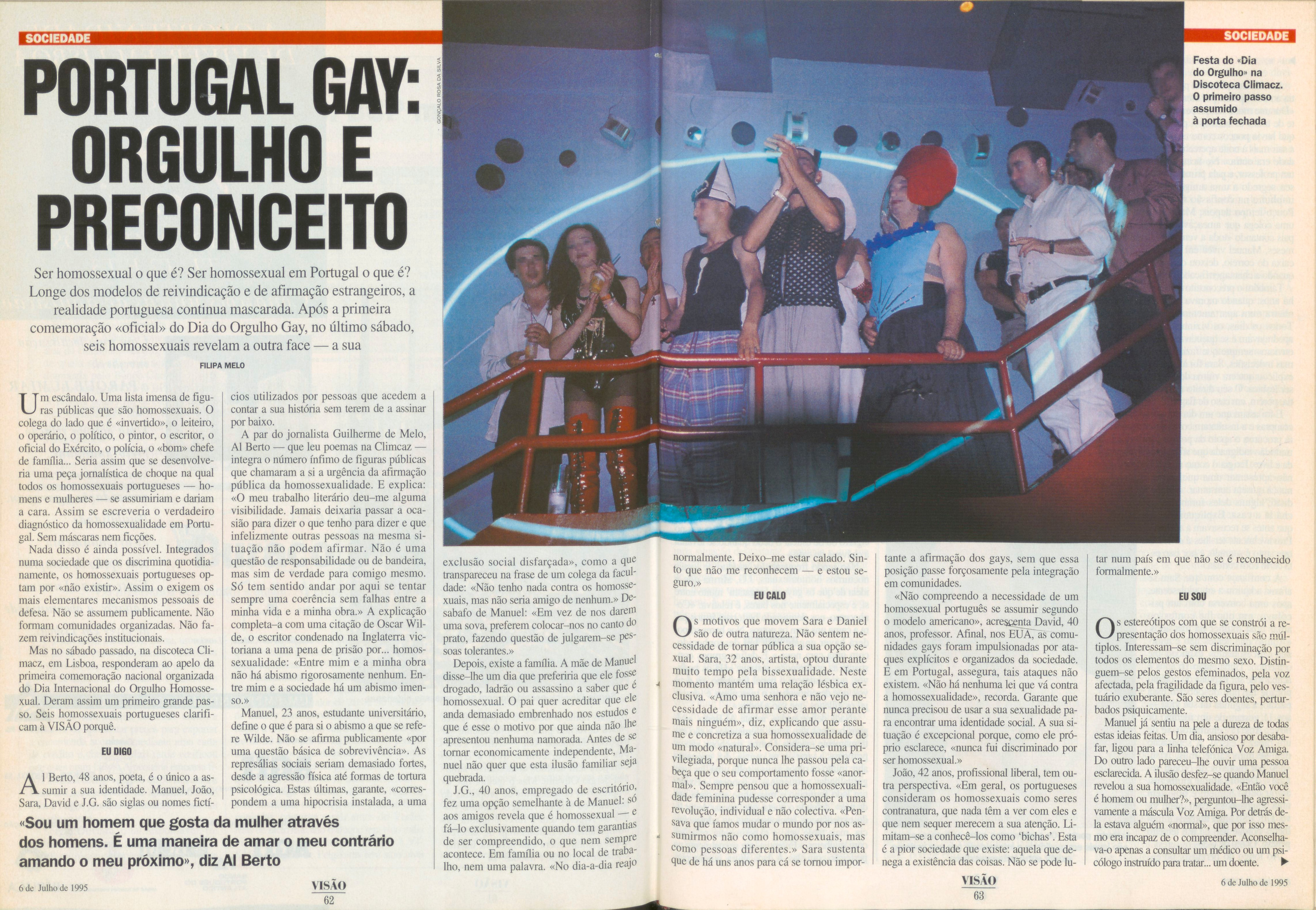

The questions were directed to all those who on the evening of July 1st, 1995 packed the CLIMACZ basement. The walls were plastered with slogans like Ama Quem Quiseres [Love Whoever You Want], the same one Zé Carlos had marched with at the MayDay Parade in 1992 (to be confirmed), and lots of photographs of famous gays and lesbians. And on a banner, “E em Portugal, quando acontecerá?” [“When will it be Portugal's turn?”] in big red letters, alongside newspaper cuttings about Gay Pride events in other countries, on a backdrop of one of the photographs taken by Gonçalo Rosa da Silva which accompanied the article published in Visão magazine from July 6th, 1995.

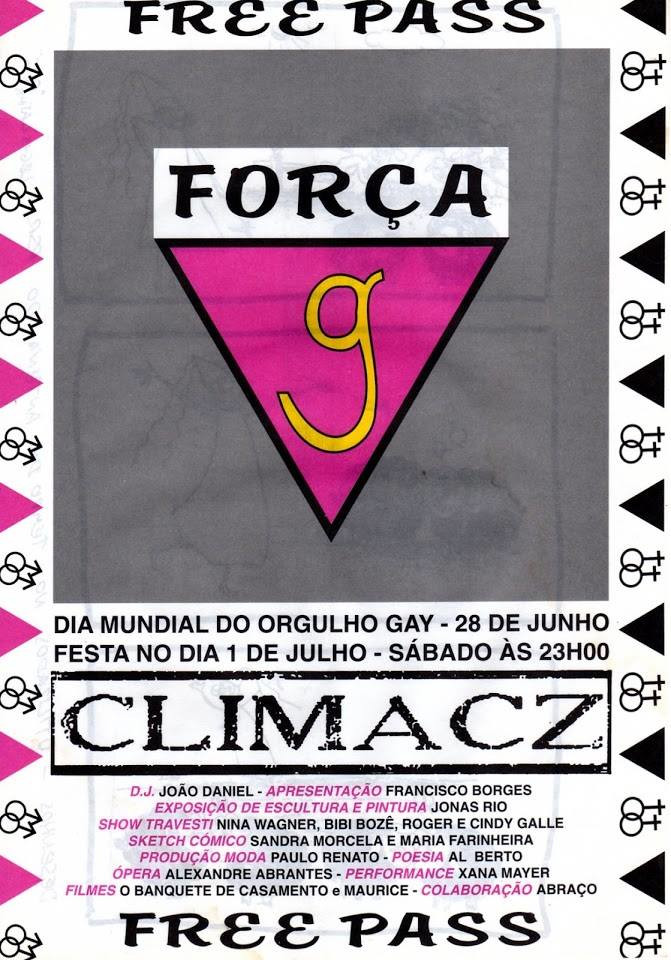

The party was set for 11 pm, handbills posted all around Lisbon streets and in the Príncipe Real gay bars. “CLIMACZ was in charge of the posters, but if you look closely,” Zé Carlos tells us, “GTH-PSR is nowhere to be seen and it was us who helped put it all together. All it says is, sponsored by Abraço. So we end up putting up all the posters, me, Margarida Martins and a bunch of other people, affixing a strip of paper which said GTH-PSR. We weren't about to throw away all the posters.”

There is a photograph by Luísa Corvo, which also appears on one of the exhibition panels for the exhibition that António Fernando Cascais, Sérgio Vitorino, Carlos Silva and members of ILGA and Clube Safo organised, Olhares (d)a Homossexualidade [The Homosexual Gaze(s)], between 2000 and 2002, where a banner placed on the façade of the Academy of Sciences of Lisbon on Rua da Escola Politécnica can also be seen. The word had to get out about the importance of that date. And the party was at CLIMACZ.

In one of the rooms there were a pair of televisions showing films, Maurice and The Wedding Banquet. “Wasn't there Lavandaria (My Beautiful Launderette) too? That's what I thought!”, Zé Carlos wonders. Maybe those three, or others. QueerLisboa, what was previously called the Festival de Cinema Gay e Lésbico de Lisboa (Lisbon Gay and Lesbian Film Festival) was still a few years away. At one of the first film bills, in 1997, at the Monument to the Discoveries, when the lights came up attendees shrank back, for fear of being spotted in the audience. That's why there are no photographs, times were different back then, not like now where everyone has their camera-ready phones, but also because people were afraid of being recognised. “Even so, the evening went quite well! We were surprised by some of those who showed up, lots of people we'd see around in our day-to-day, looking pretty relaxed and carefree. Big smiles on their faces.”

“These three CLIMACZ guys were in charge of the flyers which we were meant to post in the street and in bars, all the other bits and pieces were the GTH's job, like finding people for the drag show, which two members of the group agreed to do, and the film screening which someone else from the group also was in charge of. We invited Al Berto to recite some of his poetry. We put on an exhibition with all our materials, also including images of artists, writers and others who at the time had publicly come out, for the most part foreigners.”

“Who was it that performed in the show?”

“Fernando and Diogo, who died recently.”

“Can I speak to Fernando?”

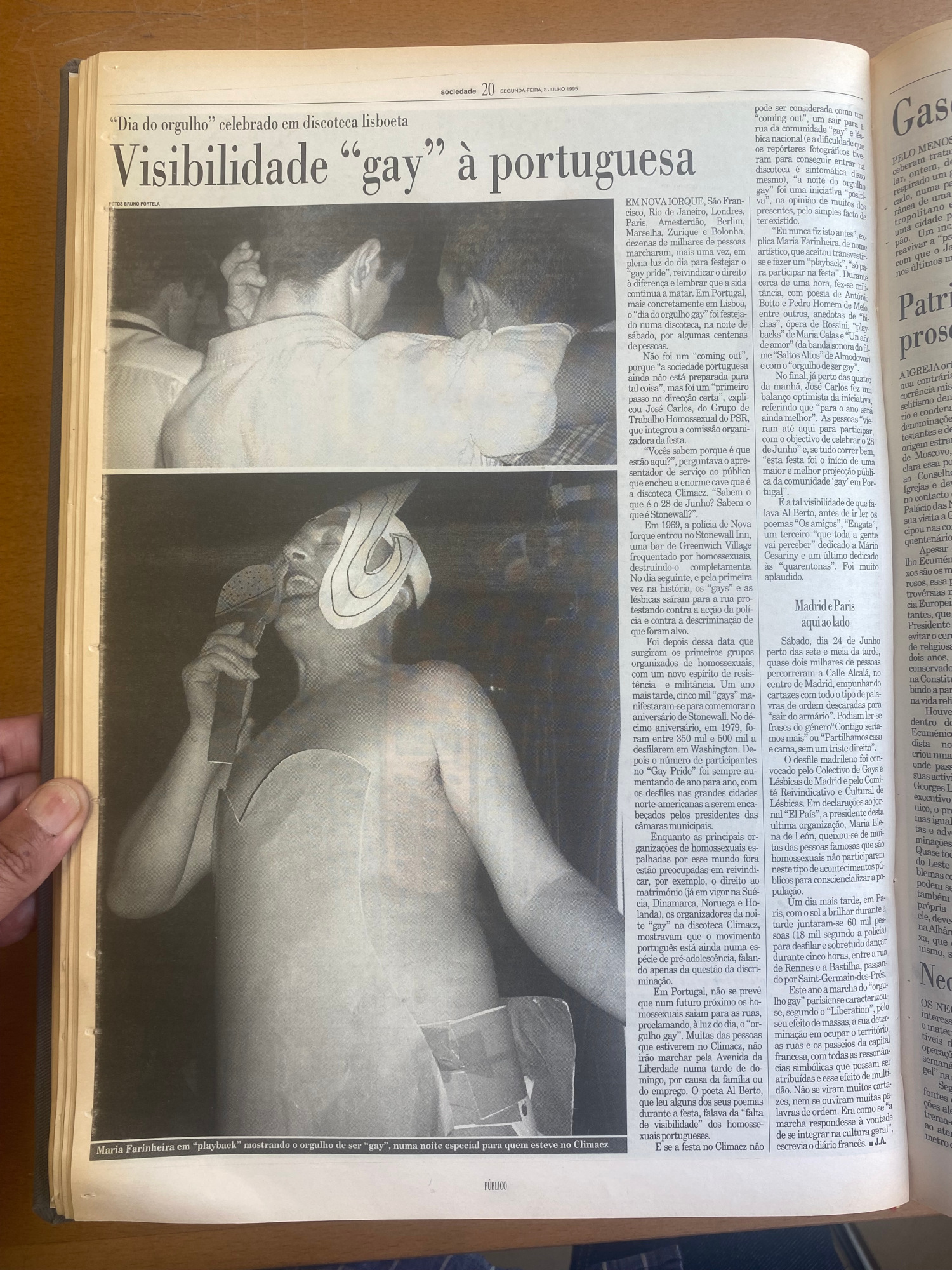

“Yeah, that's me and Quim”, confirms Fernando Rodrigues, after we sent him an image from the Visão article. “We were all in GTH together. Someone had to perform, so we just went for it. I'd seen a show by Ennio Marchetto at Teatro da Trindade, where he changes outfits real fast, in these get-ups made from cardboard, and I decided to do with same. I was called Maria Farinheira, and Quim (Joaquim Gomes) was Sandra Morcela. Morcela and Farinheira2 were our names. I made a cardboard wig and dress inspired by Madalena Iglésias. Even a microphone! You can see it in the photograph that appeared in the Público newspaper. We drew a blonde wig on yellow card and I wore a pink cardboard number which, when I turned my back, revealed a triangle. A pink triangle. No one at the time had much of an idea what that meant and I thought it important to make the reference. They didn't even know what Stonewall was... Quim was in a blue outfit, and an enormous black skirt with a bodice adorned with blue paper flowers, and a red hairdo dangling a pair of earrings also made from paper. I always liked musicals and Joaquim the opera. Joaquim sang a number by Callas. “Joaquim, I'm here with João Pedro”, says Fernando, calling Joaquim while we're having a coffee at an outdoor café on the Alameda.

“He said it was the first aria from Barber of Seville, Uma voce poco fa” I manage to make out in my scrawled

handwriting when I get home. “I had the Godspell album from the production at the Villaret Theatre with Rita Ribeiro,

Joel Branco, etc., and I thought Verónica's song, Reflete Bem, was spot on. It really was appropriate. (Verónicas

version with Quarteto 1111 plays)

We rehearsed at my place, which was just a stone's throw from CLIMACZ.”

->

The first time I spoke with Fernando Rodrigues it was over the phone, after I got in touch with Zé Carlos Tavares. Zé Carlos warned him I was about to call. After explaining my idea to him, Fernando began telling me all he could remember and I jotted down some notes. But I still was unclear about certain things, so when I spoke to him again I thought it simpler if we got together for coffee. An opportunity to get to know each other personally. Fernando showed up with Manel. “The three of them were a lot of fun!” (I'm not certain that was exactly what Manel said, but it was something like that). “They always did things like this together!” Fernando, Quim and Diogo Sotero. So that explained it. Both Sérgio Vitorino and Zé Carlos had told me Sandra Morcela was Diogo.

“It was Diogo who appeared on the cover of Visão. But not this number. Another one. Diogo didn't take part in the show during the party at CLIMACZ, but he was there. He always showed up. Lurdes and her boyfriend also were there.”

“Quim says you have a bag full of his stuff including a bunch of photos Lurdes took that night.”

“We used to all meet up at the GTH headquarters on Rua da Palma. We'd throw these parties, often with lip-sync performances that we also ended up doing at the CLIMACZ party. When the idea for the party came up, that was more or less what we had in mind. By putting on a show, we could bring together people from the group (GTH-PSR) and from outside. I'd not even met the others, I don't remember if I saw the numbers they did, we were in our dressing room and only emerged to do our bit. We ended up doing some interviews too, talking about Stonewall and what the party was about.”

“And Manel? You didn't get in drag yourself?”

“Me, no! But I handed out flyers with them. I remember Dina wouldn't let us put up a poster, or leave flyers at Memorial3. She was totally against it! On the other hand, there were bars that weren't even gay, but asked up to come back with more flyers.”

“We also did the CLIMACZ banners. It was stuff we kept back at Rua da Palma which we used in our actions. We also did those murals you used to see around.” – Ah yes, I remember those! “The photos were by Carlos Ri (Carlos Silva).”

Fernando, Manel, Quim, Carlos, Lurdes, Gabriela da Silva, Francesca Rayner, William Aguiar, Diogo Sotero... About the latter, who is talked about so fondly, they say he was the life and soul of a home for the elderly in a village near Minas de São Domingos, and passed away not ago, and is much missed. I can't stop thinking about Janu who I met on a Conga Club dancefloor, or Marum, Mariana and Jules who turned ZDB 49 into a Rabbit Hole for a QueerLisboa party and from there carried on the party in places whose names I can't even recall. Or Minas at Titanic, I never made it to Fontória, and then there's Planeta Manas, which I've yet to get to. Minas near the airport. Mina in Barreiro. The Bombshells and so many others, Arvis the party that Viegas throws and never fails to invite us to.

There's no such thing as a safe space, it's always up to us to constantly reinvent them. We also went in search of them. Hanging out outside Primas on Rua da Atalaia, where we ended up living. Capela, where we worked and where we met Fernando (was he already called Dexter back then?), Captain Kirk (we should do a project about that place) that showed films in the afternoon and Lígia serving up drum & bass all night long, followed by breakbeat and Dinis' Jungle Bells parties at Meia Cave, in Porto, and of course Frágil, always. My job interview done at Loja da Atalaia where Manel said to me, “Go be an artist” or something like that, and didn't hire me to work at Lux. Nuno meanwhile, he got in! I went to the opening of Lux with Ana Pérez. How can I expect people to tell me what the party at CLIMACZ was like, in 1995, if I can't remember a thing about the opening party Lux in 1998?

I know I was there, but I don't remember anything. I got my photo taken by Luísa Ferreira. What's there to say about the Party? There's no Fight without a Party, and we never stopped fighting. I wanted to talk about Manel Reis in this text. Let's see.

Rua Passos Manuel, no. 116-B

“It got written about in the press, and was also on television. I don't remember what channel. I actually was on the door part of the night. I remember Al Berto, it really touched me when he read some of his poems”, Sérgio Vitorino, who took over the GTH-PSR after Zé Carlos left in 1995, says to us. “Well, that photograph can't have been taken that day, but from the clothes and the general feel I'd say it's about that time. I'm also sending you this article from Público newspaper, but the print quality's not up to much.”

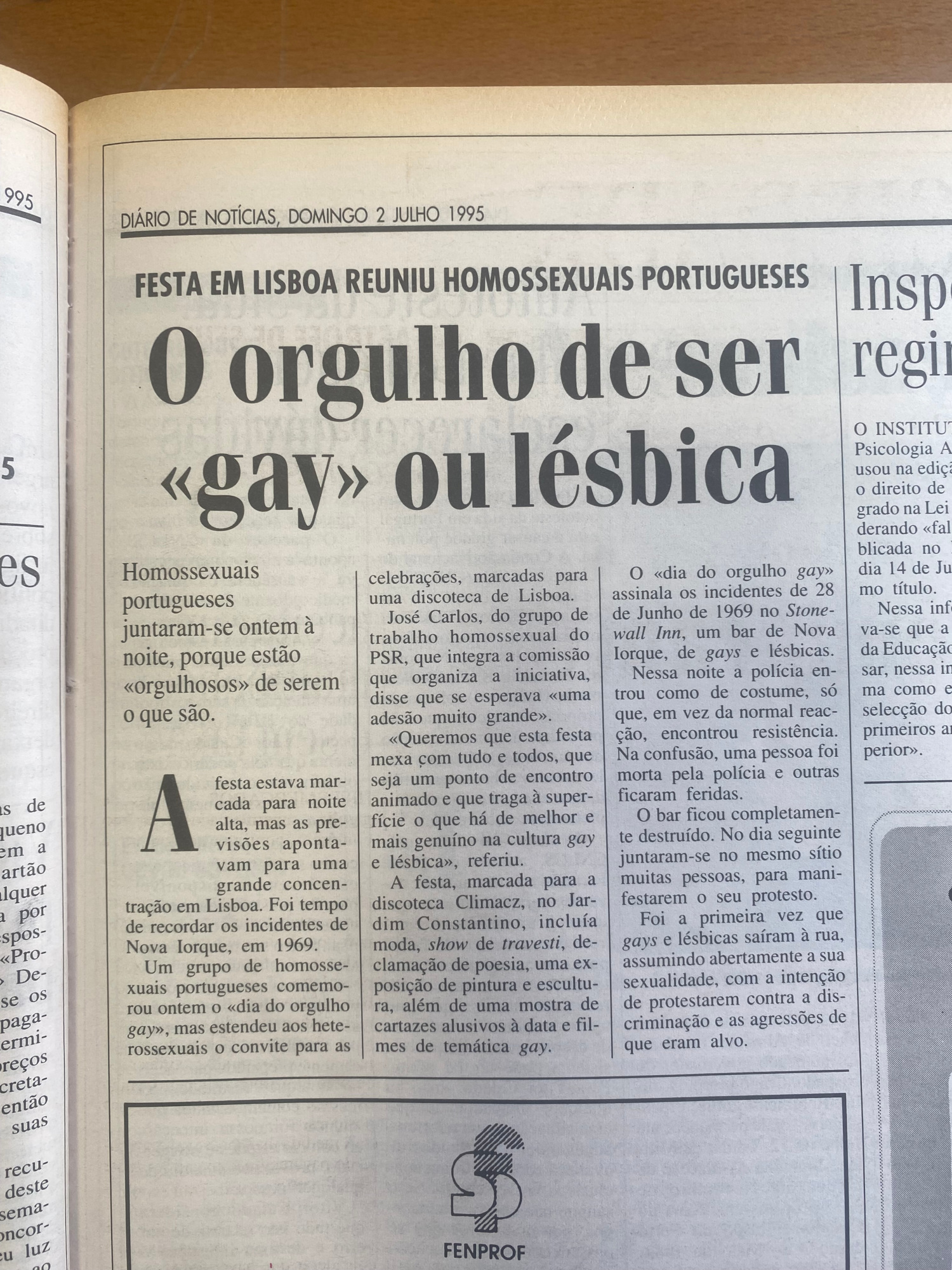

If the Público wrote about it, then other papers must have too, I thought to myself. The Hemeroteca's the place to find stuff like this, and so off I went. On my trips to the Hemeroteca, I managed to find references to the party at CLIMACZ – on the cover of the Expresso newspaper, July 1st, 1995; in the Semanário, July 1st, 1995, p.20; Diário de Notícias, July 2nd, 1995, p.21; in the Público, July 3rd, 1995, p.20; for the cover story of Visão no. 120, July 6th, 1995, cover and pp.62-65. I also checked out – although I didn't find any mention - Correio da Manhã, Jornal de Letras, A Capital, Tal & Qual, O Independente, Jornal de Notícias and Blitz in the weeks before and after July 1st, 1995. I didn't get a look at either Lilás or O Crime, for what it's worth, from the list of publications available at the time.

The Público article had the most information. What the slogans were, how happy Zé Carlos was by the end of the night, convinced it was a step in the right direction, which it was. Two years later, ILGA already up and running, it was the first ever open-air arraial LGBTQIA+ gathering (at the time it wasn't called that) in the gardens of Príncipe Real in 1997, and we were there with Ana Pérez, at the Primas stall.

“It wasn't a coming out parade, because Portuguese society wasn't ready for that yet, but baby steps, Zé Carlos Tavares of the GTH-PSR, part of the organising committee of the party, said”, went J.A.'s article in the Público of July 3rd, 1995, the Monday after the party.

I always think of Alexandre Melo, who came up with the memorable phrase we stole for this project – “I know I was there, but I don't remember anything! José Ribeiro da Fonte said going to that party was his coming out. Yeah, right! Everyone knew we were gay!”

“In Portugal, the idea that in the near-future gays might take to the streets, declaring, in broad daylight, their “gay pride” is unimaginable. Many who went to CLIMACZ weren't about to march down Avenida da Liberdade on a Sunday afternoon, because of their family or job. The poet Al Berto, who read some of his poems during the show, would talk about “the lack of visibility of Portuguese homosexuals” (I get emotional just transcribing this), the article going on to say, “And while the party at CLIMACZ cannot be considered a “coming out parade”, a taking to the streets for the gay and lesbian community of the country (and the difficulty our photojournalists had in getting through the door was proof of this), this night of gay pride was a positive initiative in the opinion of many of those who were present, for the simple fact that it had existed.”

The only picture we have of Fernando is this one. The photo was taken by Bruno Portela. I sent him a message. Let's see if he gets back to me. As for the guy from Visão, he stopped picking up the phone when he figured out I was a royal pain in the rear, after photos that were more than 30 years old. We get the gist, Fernando told us all he could, but nothing beats a colour photograph, and that's a fact. (Curious to see if one of those revealed some detail or other we weren't aware of).

“More or less an hour was devoted to militant speeches, along with readings of the poetry of António Botto, Pedro Homem de Melo and others,” no doubt from Canções (Songs), but which? And the latter's O Rapaz da Camisola Verde (The Boy in the Green Shirt) – (add poems to the end of the text and the link online) – “gay jokes, opera by Rossini, lipsyncing to Maria Callas and Um año de amor (from the soundtrack of Almodovar's High Heels), all with evident gay pride”, the article goes on. We know now that the reference to Callas was Quim's Sandra Morcela, at least. On the poster, the name of Alexandre Abrantes appears, for the opera, but we never managed to track him down. In the meantime, maybe Zé Carlos, has some idea.

“I think Alexandre Abrantes was an actor from the Comuna crowd, a friend of João Mota's and Carlos Paulo. I think he was the one living in Amadora. He had a great singing voice, he did all his own singing, live.”

“And Paulo Renato, what about him? That's another one I've yet to figure out.”

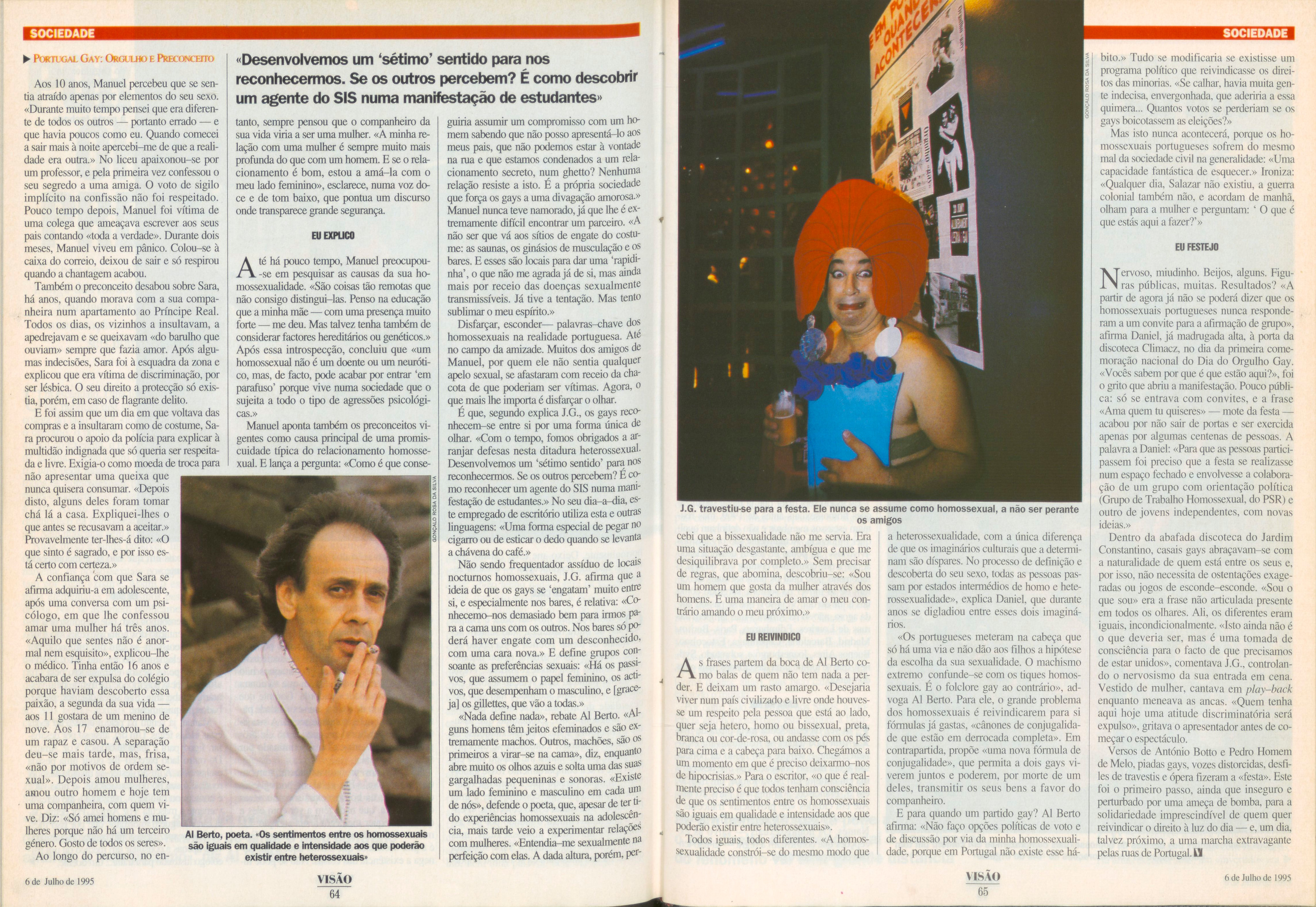

“Paulo Renato did at little fashion show. So gay! It's Jonas who appears in the group photo for the Visão article. He must have been in the fashion show as well, from what he's wearing, whoever's with Quim has to have been asked to take part.” That makes sense, I thought, there's something Manobras de Maio4-looking about the whole affair.

“Don't forget to mention the condoms.” Zé Carlos insists when we finally manage to get a coffee in Charneca da Caparica. “We handed out condoms with the help of Abraço. It was important to get the word out that the community had to stay healthy.” I can't look at Zé Carlos today without it reminding me of when he dressed up as a condom in Rossio in 1992, on World AIDS Day. (footage RTP). “It was Fernando Rodrigues who painted the banners.” Fernando aka Maria Farinheira.

Jenny Larrue didn't hesitate when she said: “The only name that rings a bell is Nina's. The rest I have no idea.” Fernando Santos, aka Deborah Krystal, says the same - and goes on to add “I actually worked at CLIMACZ, some time later. And I took part in the first arraial in Príncipe Real”. I knew that, or to be more precise, I was there, but I don't remember anything. That again.

Deborah told me to speak to Rogério d'Oliveira. He was the one who organised the first arraial stage show, maybe he'd remember something. The only name Deborah recalls is Nina Wagner's, “but forget it, you won't get to speak to her, she ended up distancing herself from the likes of this.” Rogério didn't go to the party at CLIMACZ. He worked on the arraial and at the ILGA opening. Now he's more of a “day-owl”, he tells me when we exchange messages. I know what he means! (duh, JP).

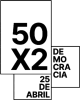

On the poster Nina Wagner, Bibi Bozé, Roger and Cindy Galle – were the star attraction in the Drag Show, but except for Nina, who we spotted in a bunch of photographs on the page of a Facebook group (Príncipe Real anos 60, 70, 80) we couldn't get any further. The comedy sketch by Farinheira e Morcela, check! The fashion show, Paulo Renato, semi-check! Poetry: Al Berto.

“As the party wound down close to four in the morning, Zé Carlos was positive about how well the event went, saying that “next year it will be better”. People “came to take part in celebrating June 28th” and if all goes well, “this party was the beginning of a bigger and better public profile for the gay community in Portugal”. It's the same visibility Al Berto was talking about, before reading his poems - Os Amigos, Engate, a third one (“which everyone will understand” dedicated to Mário Cesariny) and one more dedicated to all the “quarentonas” (ladies in their forties). It brought the house down.

PS: Halfway through the month of November, long after the project was launched at Appleton, I received a message from Bruno Portela. “João Pedro, these were actually printed photographs and I have nothing digitalised. I for sure have more photos from that day.” I'd reached out to Bruno via an address he rarely checked. We ended up having a chat over the phone and by December, close to Christmas, he got in touch again Bruno had found the negatives of the photos from the party, as a matter of fact a box with a series of rolls labelled “Noites Clandestinas” [Clandestine Nights]. Just like Captain Kirk, there's enough material here for another project. We got digital copies made of the roll and a few days later we ended up with a set of 27 colour digitalised photos, which Bruno then edited and are now available HERE. Photos were generally taken as colour negatives but then printed in black and white, as happened in the Público newspaper article (I agreed with Bruno Portela that they would now be made available in black and white). We were able to finally see, in colour, Fernando “Farinheira” and Quim “Morcela” with their cardboard outfits, Al Berto reciting his poems, some of the performers and members of the public, and friendly faces such as Fernanda Câncio Maria João Guardão, and Alexandre Melo, who it's true, may not remember anything, but he went, he was there. I know I was there, but I don't remember anything!